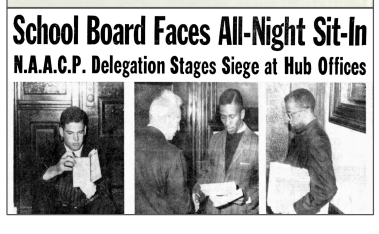

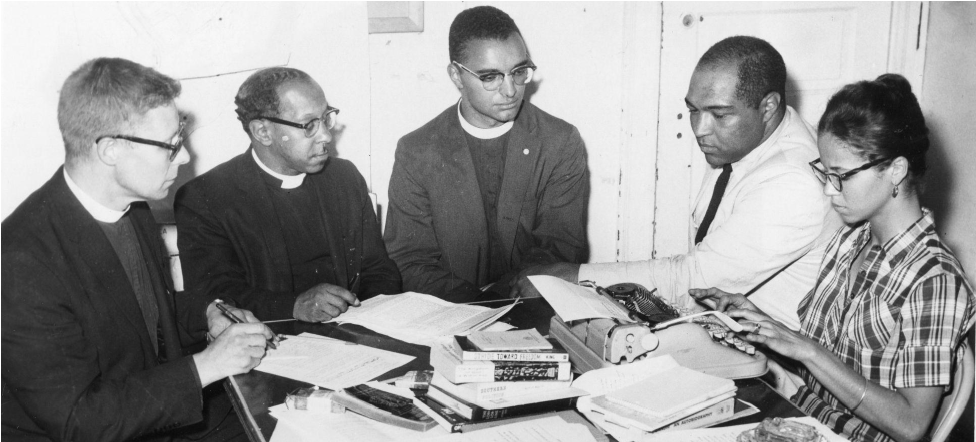

In the 1960s, the Boston School Committee was a stubborn opponent to Black community activists. In the face of growing protest, the elected group chaired by Louise Day Hicks denied that Boston Public Schools were segregated at all. On June 14, 1963, Ruth Batson testified before the Committee as the chair of the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination. Batson and other experts shared research and examples showing stark disparities between schools attended exclusively by Black and white children. Their fourteen demands began with “a public acknowledgment of the existence of de facto school segregation in the Boston Public Schools.” The grueling seven-hour hearing failed to persuade the Committee. It was a worst-case scenario. But the NAACP, under the leadership of president Melnea Cass, had prepared for it with a bold plan.

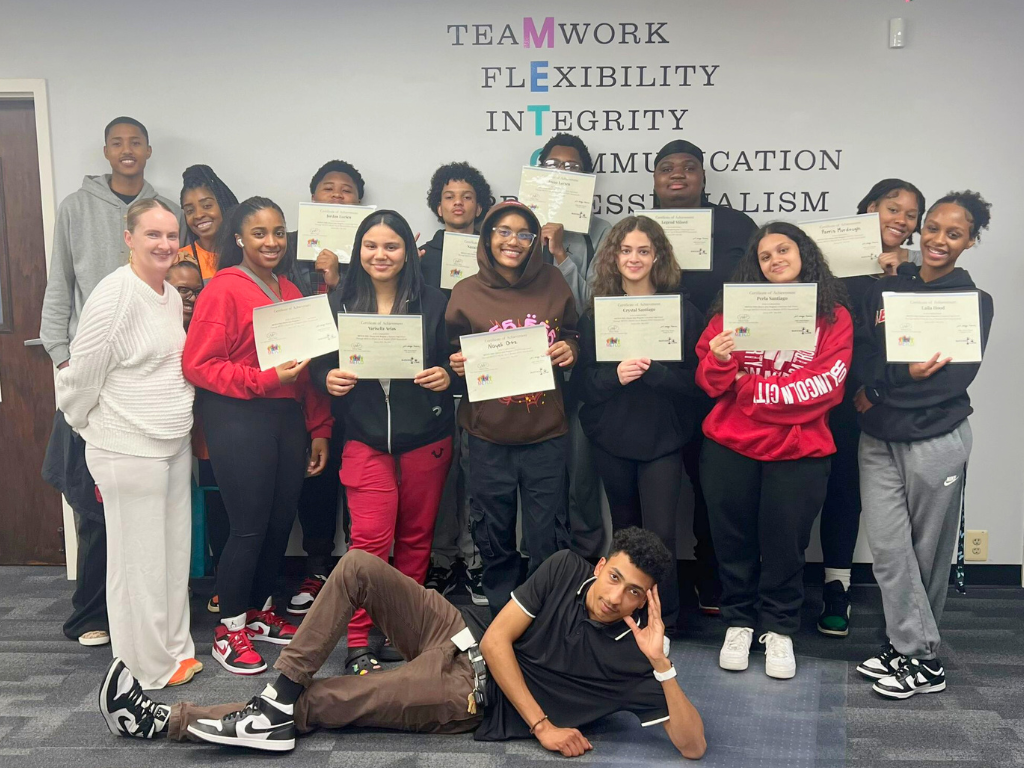

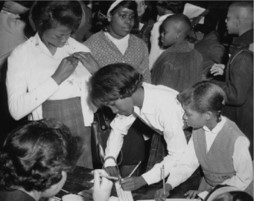

Roxbury residents of all ages staged creative acts of civil disobedience to affect change.

In the days after the School Committee refused to discuss their demands, the NAACP and other community groups sprang into action. Demonstrators like Rev. Vernon Carter picketed and held sit-ins at the School Committee building. The following week, a much larger mobilization began: a school boycott involving 30% of Boston high school students. This Stay Out for Freedom, led by former Dartmouth roommates Noel Day and Rev. James Breeden, was more than a walkout: parents, grandparents, teachers, and church leaders put together dozens of pop-up Freedom Schools all over Roxbury, providing lessons on Black history, citizenship, non-violence, and civil rights. They mounted an even larger Freedom Stay Out in February 1964, with 10,000 Black students and 1,000 white students from Wellesley, Weston, and other suburbs. These strategies did not lead directly to change, but the relationships they forged laid the groundwork for future breakthroughs.